-

Who We Are

Who We Are

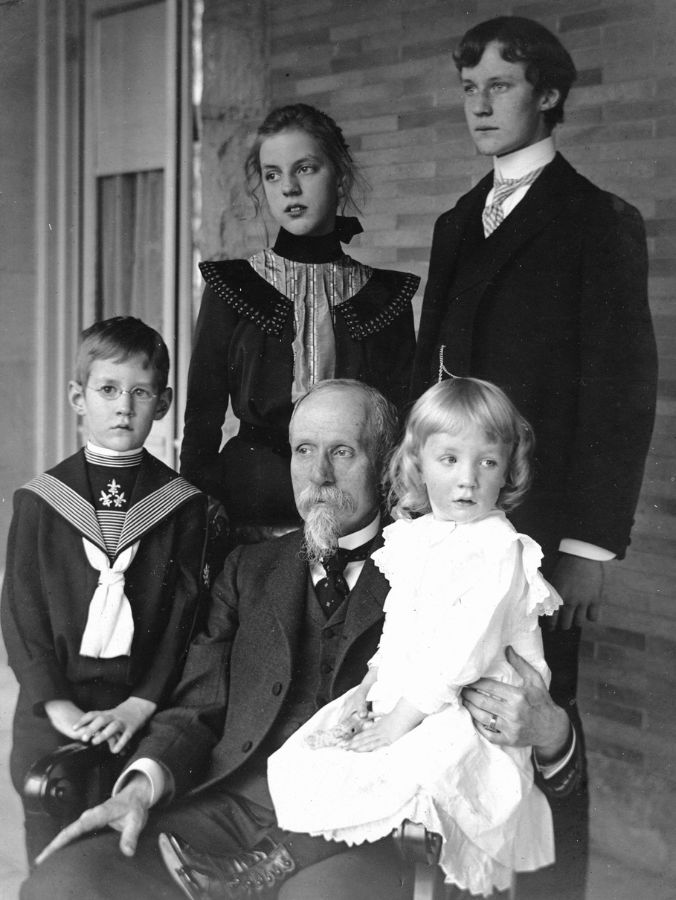

For the last century, we’ve dedicated ourselves to empowering families like yours to prosper and endure. Like many of the leading families we serve, we have been through our own wealth journey.

Discover Pitcairn -

What We Do

Wealth Momentum®

The families we serve and the relationships we have with them are at the center of everything we do. Our proprietary Wealth Momentum® model harnesses powerful drivers of financial and family dynamics, maximizing the impact that sustains and grows wealth for generations to come.

Explore - Insights & News

One of my standard questions for clients when drafting their estate-planning documents has been: “Do you have any special needs individuals in the family?” Today, I’m able to acknowledge how leading that question is. The more accurate question should be, “Since it’s common for a family member to have special needs such as autism, should we plan for this situation in your documents?”

According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, there are approximately 13% of the civilian noninstitutionalized population (about 42.5 million Americans) with disabilities. This broad spectrum of data includes disabilities from the severe (those unable to perform activities of daily living) to the less severe (sensory or mobility issues that don’t impact activities of daily living).

It’s important to note that the Census Bureau figures don’t include those on the autism spectrum. According to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control, autism affects almost one-third of all children in the United States today, and those numbers appear to be rising.

Advantages

Many practitioners ask clients if there are any special needs individuals in the family when gathering the data necessary to draft an estate plan. What’s important though is that the special needs planning doesn’t end with the answer “no.” Unless there’s an extreme need in the present, such as to care for a child born with debilitating physical ailments, many advisors likely ignore the importance of setting up a special needs trust (SNT). But, that could be a mistake, particularly when planning for multi-generational wealth. When dealing with ultra-high-net-worth clients with multi-generational wealth, there’s a strong likelihood that, if not now then at some point in the future, there will be someone in the family with special needs. In my own work, I’ve found a growing number of clients who tell me they have a grandchild with special needs. For them, the current need may be apparent, but for others, drafting with flexibility will allow for the creation of an SNT at a future date.

SNTs can provide numerous advantages for beneficiaries. The main objective is to support the beneficiary without jeopardizing their eligibility for public benefits such as Medical Assistance. The SNT’s assets can be used to pay for out-of-pocket expenses including, in part, travel, entertainment, pet care and other expenses that could improve the quality of life for the beneficiary.

Future Need

There doesn’t have to be an immediate need in order to draft an SNT into a document. A client can create a multi-generational trust today and name the beneficiaries, some of whom may not yet be born. The trust may provide that in the event that a beneficiary is diagnosed with a special need then certain provisions will apply. This can ensure that the trust won’t hinder the receipt of public benefits. I typically see this type of language in testamentary trusts in which grandchildren are the beneficiaries.

Another method to allow for the future creation of an SNT, specifically for when the provisions of the trust are silent is to draft trust protector language into the document providing the protector with the power to create or carve out an SNT. A trust protector serves as an additional advocate for the beneficiary alongside the designated trustee. The protector’s role can be limited or broad enough that the provisions allow them to modify the trust as necessary to take into consideration a beneficiary’s special needs.

From time to time, I run into lawyers who don’t, and never have, drafted trust protector provisions into trusts. Nevertheless, this role has been available for decades. Based on my experience working with trusts situated throughout the United States, it seems that the use of trust protectors may also depend on the jurisdiction. If as an advisor, you find yourself working with an attorney who’s reluctant to draft a trust protector role it would be best that you ask questions. Keep in mind that a trust protector can also serve as a second set of eyes that can be particularly helpful when the beneficiary is still a minor. The protector can ensure that the minor beneficiary is properly clothed, their education is taken care of and that they’re going to a camp that can accommodate their needs.

Decanting an Irrevocable Trust

If the grantor of the trust made the individual with special needs the beneficiary of an irrevocable trust in which the trustee is required to make distributions of income or principal rather than qualifying the trust as an SNT, the beneficiary could be denied certain public benefits until the trust assets are spent down. But decanting may be an option to cure a non-SNT.

Decanting is a method in which a new trust is created by pouring the assets of the original trust into the new trust vehicle. The new trust would then have the provisions necessary to qualify the trust as an SNT. Although tax and other considerations should be researched prior to decanting, especially if the trust is generation-skipping, decanting can offer a solution.

As I noted at the outset, special needs individuals may not exist in the current family structure but there’s a strong statistical probability that this may not be the case in the future. Careful and thoughtful drafting to provide flexibility within a trust should be considered and it should be part of any advisor’s multi-generational planning tool kit.

Disclaimer: Pitcairn Wealth Advisors LLC (“PWA”) is a registered investment adviser with its principal place of business in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Additional information about PWA, including our registration status, fees, and services is available on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. This material was prepared solely for informational, illustrative, and convenience purposes only and all users should be guided accordingly. All information, opinions, and estimates contained herein are given as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. PWA and its affiliates (jointly referred to as “Pitcairn”) do not make any representations as to the accuracy, timeliness, suitability, completeness, or relevance of any information prepared by any unaffiliated third party, whether referenced or incorporated herein, and takes no responsibility thereof. As Pitcairn does not provide legal services, all users are advised to seek the advice of independent legal and tax counsel prior to relying upon or acting upon any information contained herein. The performance numbers displayed to the user may have been adversely or favorably impacted by events and economic conditions that will not prevail in the future. Past investment performance is not indicative of future results. The indices discussed are unmanaged and do not incur management fees, transaction costs, or other expenses associated with investable products. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Projections are based on models that assume normally distributed outcomes which may not reflect actual experience. Consistent with its obligation to obtain “best execution,” Pitcairn, in exercising its investment discretion over advisory or fiduciary assets in client accounts, may allocate orders for the purchase, sale, or exchange of securities for the account to such brokers and dealers for execution on such markets, at such prices, and at such commission rates as, in the good faith judgment of Pitcairn, will be in the best interest of the account, taking into consideration in the selection of such broker and dealer, not only the available prices and rates of brokerage commissions, but also other relevant factors (such as, without limitation, execution capabilities, products, research or services provided by such brokers or dealers which are expected to provide lawful and appropriate assistance to Pitcairn in the performance of its investment decision making responsibilities). This material should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. This material is provided for information purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase an interest or any other security or financial instrument.